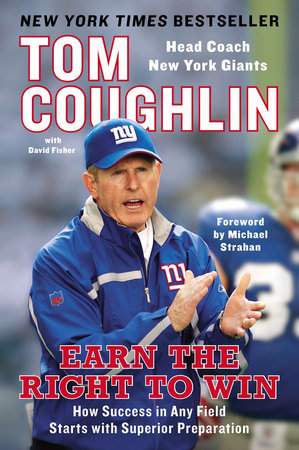

Tom Coughlin, with David Fisher: Earn the Right to Win. How Success in Any Field Starts with Superior Preparation. Foreword by Michael Strahan. NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2013. 210 pp.

Earn the Right to Win is less a football memoir than a guide on how to succeed through meticulous preparation. Gridiron fans may find it heavy on the management side, while business types might give this a read if they are ready to peer over the rim of the sandbox. The ideal audience seems to be business people who like the game.

The arrangement is topical, not chronological. That is, we do not follow Tom Coughlin’s career beginning at Rochester Institute of Technology through to the NY Giants; rather, we get his thoughts on preparation, scheduling, the importance of attention to detail, effective communication, motivation and practice.

Coughlin has heard himself criticized for being too regimented, but takes it as a compliment. Again and again he stresses the value of making a schedule and sticking to it. “Having an established system that people can rely on makes it a lot easier to keep them from losing focus, becoming anxious, being depressed, even panicking when something goes wrong.” In other words, he sees it as something that benefits primarily the team. He leaves relatively unexamined the question whether it may also be a personal mania.

It is no secret that his great strength is a fanatical dedication to time management. “Coughlin Time” means more than just his famous rule about being five minutes early for every meeting; it also means timing practices out to the second, it means knowing what you will be doing on any given day a year in advance. “In September,” one of his assistant coaches once said in all seriousness, “I know what time I’m going to be eating lunch the following June.”

Having a short week – a game on Thursday, say, after a Sunday game – is usually regarded as a hardship, but Coughlin turns it into an advantage, because no other coach is going to be better organized or better prepared to deal with the change in routine. On the other hand, allowing both teams extra time to prepare for a game gives even the less-organized opposing coach sufficient time to prepare, which may explain why the Giants under Coughlin were not particularly successful on Monday Night Football. Though they did okay when they had two weeks to prepare for the Patriots in a couple Superbowls, as I recall.

In Coughlin’s world, consistency and stability are more valuable than inspiration and spontaneity. He cultivates an image of boring sameness, proclaiming that “predictability is an important aspect of preparation.” That last word is, of course, key. When he first came to the Giants, he worked players so hard they genuinely suspected he was trying to kill them, so much so that they bonded over their shared hatred of him – until they understood what he was after. As punter Steve Weatherford explains, “He puts pressure on us in practice so that in the game we don’t feel it.”

Moreover, as an old-school coach he actively discourages any kind of flashy displays or celebrations. His ideal is not a jazz combo but a meticulous, military-style operation (General Ray Odierno gets quoted more than once). This approach leads to tension with the current generation of players, who think it’s fine to perform their well-rehearsed sack dances even when the team is hopelessly behind. How far we have progressed since the days of Vince Lombardi, who once chewed out Alex Webster (of all people) for doing a little happy skip-jump as he ran off the field after scoring a touchdown. Coughlin might dream of doing the same, but knows better than to try.

As part of his preparation, he goes so far as to study the tendencies of individual officials – what penalties they like to call, and how often their calls are overturned. (In this, he was ahead of his time; by 2019 even TV commentators started noting which officials are flag-happy.) He sketches out where the shadows will fall on the field at different times of the afternoon. (Ben McAdoo learned this lesson well in his first game as head coach, when he beat the Cowboys in their own stadium in part because he chose the side of the stadium that left the Dallas receivers looking back into the sun in the 4th quarter.) If Coughlin could chart individual wind swirls, I’m sure he would. Who knows, maybe he does.

The book is based on a transcript of interviews that veteran co-author David Fisher conducted with Coughlin in 2012-13. This genesis accounts for the book’s somewhat conversational tone. BTW, Coach Coughlin always tends to refer to trick plays as “gadget” plays; co-author Fisher has managed to correct this idiosyncrasy to some extent, so that we read about “gadget or gimmick plays.” Since the book came out, “gadget plays” has become an accepted part of football jargon. In a non-football context, a gadget is a small mechanical or electronic device, especially an ingenious or novel one – in other words a kind of thing, not an activity.

One reviewer has claimed that coach lacks humor, but in fact he does manage a little of the understated variety, usually when talking about his long-suffering wife. He says for instance that the two of them “made a contract” about how many days he would spend with her away from the office. “Admittedly, I have tried to renegotiate the terms of that agreement, but she has held firm. In fact, she has even lobbied – unsuccessfully, so far – that we expand it to seven days” a year. For her part, she also manages a little levity. Once when Tom was between coaching jobs and spending significantly more time at home, she learned an important lesson: “One thing we found out that year was that I was not anxious for him to retire.”

To be precise, the unexpected free time came after Coughlin was fired at Jacksonville despite being the best coach that franchise ever had. Typically, he used the opportunity to prepare himself for his next head-coaching position – without knowing where that would be, or even if he would ever be given another chance. Nonetheless, his confidence was so high he turned down Bill Parcells’ generous offer to be one of his assistant coaches and kept on preparing himself as if he knew he was soon going to be pacing the sidelines again. This kept him mentally sharp during the unwanted break, so he was ready when the call came offering him the top job with the Giants. Steve Spagnuolo did much the same after he was fired, spending 2018 watching film every week to stay current.

Coughlin shares quotes taken from the John Wooden school of motivation that will resonate with many readers, who may want to copy them down for their own reference. Amazingly, even Eli Manning, a master at avoiding any utterance worth remembering, offers a pithy comment: “Preparation is addiction.” Here’s one from Coughlin that I liked: “The simple phrase, You can do better than that, spoken by someone you respect, is about as good a motivational tool as has ever been discovered.” Likewise, there is no better reinforcement than a compliment – and not just “Thank you” but “Great job.”

A final note. Something that Coughlin never really addresses is this basic truth: On average, the team with more talent is more likely to win, so long as the coaching is at least competent. Not being a general manager (at least at the time this book was written), Coughlin tends to believe his edge comes through meticulous preparation, not through selecting the better players. Indeed, one topic conspicuously absent from this book is the spotting and recruitment of gifted athletes. It’s true that when facing an opposing team with roughly equal talent, preparation can provide an edge. But when facing one of superior ability, even the most thorough prep can do no more than allow you to be competitive, to stay in the game until the end. He reminds us that the Giants’ team motto back in 2010 was “Finish,” which shows that the problem of holding onto leads hasn’t been a new one for subsequent coaches (McAdoo, Shurmur, Joe Judge).

Indeed, this is what we all saw over and over in Coughlin’s final season: Even though his team could boast only a single Pro Bowl player (JPP), it was usually in the game – until the final two minutes.

Related post: See my review of Michael Lewis’s Moneyball elsewhere on this site.

© Hamilton Beck