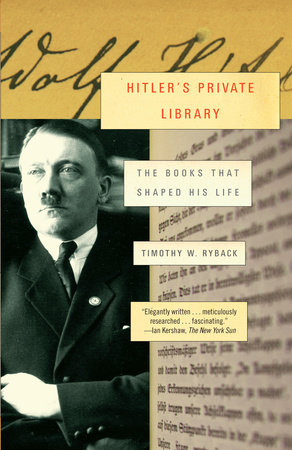

Timothy W. Ryback: Hitler’s Private Library. The Books that Shaped His Life. NY: Vintage, 2010. 300 pp. Ill.

First some statistics. At his death, Hitler’s library consisted of some 16,000 volumes, of which it seems only around 1,300 have surfaced, many of them in the Library of Congress. Eighty volumes are housed at Brown University in Providence, RI. Others are scattered across the US and Europe. The original shelving system has of course been lost. So what we are dealing with is not so much Hitler’s actual library as some remnants of it. Parts might be lost forever.

But not all; in the course of time, more may well turn up. In the early 2000s I recall seeing a complete set of the Brockhaus Encyclopedia on a shelf in the reference section of the state university in St. Petersburg, handsomely bound in leather. When I opened volume H, I was startled to see on the inside cover a stamp of an eagle grasping a swastika. The set had been taken – doubtless in 1945 – from the Interior Ministry in Berlin, not the Führerbunker, and it was of course not Hitler’s personal copy. But it would hardly be surprising if such books were eventually to turn up. After the war, the library of the Reich Chancellery was shipped to Moscow, where it was put into storage; after briefly resurfacing in an abandoned church in the 1990s, it disappeared again.

Another personal experience. A few years earlier – ca. 1996 – I came across some wartime issues of German newspapers spread out on a table in the state archives in Chisinau. As long as Moldova was part of the USSR, they had been stored but never catalogued; it looked like now at last that process could begin. I carefully copied out by hand some reviews of Nazi films from a paper published in Thorn, Poland, figuring these were unlikely to be known. When the librarian finally noticed what I was doing, she swiftly removed them after throwing me a dirty look, thus proving something I have often observed: If librarians in America try to help visitors find information, the attitude in Russia (Germany, Moldova, and indeed Europe generally) is quite different; there, librarians seem to think it is their job to protect books from readers. My point is, there might well be many resources listed as “lost” that have in fact survived, and more volumes from Hitler’s library may be among them.

Timothy Ryback had made it his task to examine the stories these books – and their marginalia – tell. He delves into them and their authors, many of whom are likely to be unfamiliar to readers in the English-speaking world. His approach is primarily chronological by date of acquisition. As far as is known, the earliest surviving book Hitler bought was Max Osborn’s guide to Berlin, published in 1909, which he purchased in late November 1915 at a bookstore in Tourney, France, just two miles behind the front-line trenches there. Osborn, a prominent cultural critic of the time, looks at first glance like he might be worth re-discovering, though his Prussian patriotism, which veered into chauvinism, would ruffle feathers today. He also wrote a book about the Western Front: Drei Straßen des Krieges (Berlin, 1916), dealing with Arras, Champagne, and Flanders, but there is no evidence Hitler owned a copy. Because Osborn was Jewish, he later had to emigrate, ending up in New York, where his memoirs were published with a foreword by Thomas Mann. He died in 1946.

It is in Osborn’s guidebook that Ryback discovered an inch-long hair from Hitler’s mustache, a detail that is almost invariably brought up in reviews, though to my knowledge no one has suggested subjecting this hair for DNA analysis to see what it might reveal. The mention of Hitler’s fingerprints has attracted less attention.

To judge by his book purchases, Hitler’s hatred of the Jews dates from the early post-war years, when he came under the influence of Dietrich Eckhart, publisher of “the hate-mongering weekly Auf gut deutsch (In Plain German).” (pg. 30) Later, Ryback provides a useful list of the anti-Semitic readings Hitler recommended, including of course Houston Stewart Chamberlain’s Foundations of the Nineteenth Century and Henry Ford’s The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem. (pg. 50ff)

An autodidact since dropping out of high school, Hitler read voraciously, consuming one book per night. When it comes to literature, he seems to have preferred Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to the German classics, Goethe and Schiller. His real favorite, of course, was Karl May, and he enjoyed crime and adventure stories. (See Das Buch Hitler which says that in the summer of 1939 on the Obersalzberg Hitler would often withdraw to read crime and adventure stories [pg. 102]; this is mistranslated in the English version, The Hitler Book – reviewed elsewhere at this site –, to say that it was Eva Braun and her lady-friends who enjoyed such reading [pg. 45].)

Ryback points out that on the whole, Hitler seems not to have read much for enjoyment, nor to broaden his outlook. Rather, he read to reinforce; that is, he scanned texts for arguments and facts that agreed with his pre-conceived notions, always looking for mosaic pieces that would fit into a larger pattern, discarding the rest. When he came across something that jibed with his world view, he would add it to his storehouse of evidence. Reciting facts is always a good way to impress Germans, since they want to believe they are listening to reason.

I would also suggest that Hitler’s interest in Jewish world conspiracy theories, and occult foolishness involving “incontrovertible proof” of supernatural events, were part and parcel of his being an autodidact. Not to say that all autodidacts believe in claptrap, far from it. But some of them, like other poorly educated folk, cannot distinguish sense from nonsense, science from pseudo-science. Though he does not make much of it himself, the danger of the autodidact is a recurring theme of Ryback’s. Later in the book, for instance, it comes as little surprise that Hitler admired Carlyle’s portrait of Frederick the Great; Ryback quotes William Butler Yeats, who once called Carlyle “the chief inspirer of self-educated men.” (pg. 229)

If Books Could Kill — Mein Kampf

Turning to Hitler’s own books, Ryback pays close attention to the opening paragraphs of Mein Kampf, but little thereafter. He does examine early drafts, finding them full of elementary errors (not just typos). Hitler often misspelled the name of one of his supposedly favorite philosophers, Schopenhauer. I say “supposedly” because Hitler’s essential core, as Ryback says, was “less a distillation of the philosophies of Schopenhauer or Nietzsche than a dime-store theory cobbled together from cheap, tendentious paperback and esoteric hardcovers, which provided the justification for a thin, calculating, bullying mendacity.” (pg. 183)

Though Hitler most definitely labored over Mein Kampf, in the end it is unlikely that many people found the patience to read more than a few dozen pages. It is typical that he originally wanted to give it the long-winded title A Four and a Half Year Battle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice. It was his publisher, Max Amann, who shortened this to Mein Kampf (My Struggle), a much better choice.

Hitler’s speeches might have been effective delivered in a beer hall packed with believers, but his book offered little to contemplative readers. Even party philosopher Alfred Rosenberg, no stylist he, dismissed Mein Kampf as unreadable. By the way, Hitler returned the disdain. Rosenberg once presented him with a copy of his dense and woolly Myth of the 20th Century; like virtually everyone else, Hitler was unable to get past the first pages.

One more thing about Mein Kampf – I can personally attest to its unreadability. Back in 1978-79, when I was working at Mary S. Rosenberg’s German-language bookstore in Manhattan, I came across some shelves in a back room holding a collection of anti-Semitic literature. This had formed part of the stock for the family’s shop in Fürth, near Nuremberg, in the 1920s and early 30s; the Kissinger family had been regular customers, as Mrs. Rosenberg proudly informed me. Finding an abridged translation of My Struggle published before the war, I settled down to read it during my lunch hour, but soon gave up. It is hard to imagine anyone who does not have to plowing all the way through this turgid book.

US Connections

In the early postwar years, Hitler regarded the USA as some kind of Nordic Union. With time, though, he came to think of Americans as a mongrel race, whose inferiority meant they would inevitably succumb to the Aryans. This helps explain why he so cavalierly declared war after Pearl Harbor.

As it happened, many of the leaders in the attempt to use eugenics to create a master race turned out to be Americans, such as Madison Grant, whose degree from Columbia was in law; Leon Whitney, author of The Case for Sterilization; and Charles Davenport (professor of zoology, Harvard). Likewise Paul Popenoe majored in English with coursework in biology; an expert in dates, he later edited the Journal of Heredity. While it’s not clear if Hitler owned their books, he was familiar with their work. Lothrop Stoddard (whose Harvard Ph.D. was in history) was actually granted an audience with the Chancellor himself in December 1939. Ryback doesn’t mention it, but Stoddard also conferred with Goebbels and Himmler on this occasion. Moreover, he was the model for “Goddard” in The Great Gatsby, described there as the author of The Rise of the Colored Empires; Stoddard had in fact penned The Rising Tide of Color against White World Supremacy (1920). Stoddard kept his word and never revealed the substance of his conversation with Hitler.

By the way, in the movie “Remains of the Day” this is the book Lord Darlington is reading before he decides to order the dismissal of the two servant girls — Jewish refugees. For more on the influence of American eugenicists, including Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard, see James Q. Whitman: Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. (Princeton UP, 2017) See also the article by Paul A. Offitt, “The Loathsome American Book That Inspired Hitler” in “The Daily Beast,” August 26, 2017. “To say that [Madison Grant’s] The Passing of the Great Race had influenced Mein Kampf would be an understatement; in some sections, Hitler had virtually plagiarized Grant’s book.” http://www.thedailybeast.com/the-loathsome-american-book-that-inspired-hitler

Also this from Bret Stephens (NY Times, January 18, 2018):

Just as Donald Trump wants more Norwegian immigrants and none from “s-hole countries,” the early 20th-century eugenicist, conservationist and immigration restrictionist Madison Grant was obsessed with protecting the “Nordic” races against those he termed “social discards” — including “the Slovak, the Italian, the Syrian and the Jew.”

Tangents

Thankfully, Ryback does not restrict himself to discussing books, for even his tangents are interesting. He pays significant attention to Bishop Alois Hudal’s attempts to reconcile Catholic theology with Nazism. These efforts, though ultimately futile, culminated in 1936 with the publication of Hudal’s Foundations of National Socialism after it received Hitler’s personal approval. Hudal inscribed a dedication of the copy he presented to Hitler with the words, “To the Siegfried of German hope and greatness.” What Ryback fails to mention is that after the war, Hudal helped Eichmann, Barbie, Erich Priebke, and other top surviving Nazis obtain visas to Argentina. It was his signature on documents submitted to the Red Cross that facilitated these “illegal movements of emigrants,” as the US State Dept. called them. According to the Wikipedia article on Priebke, Hudal “was accustomed to making false travel documents for German officials who had been involved in war crimes.”

Using the circumstance that some of Hitler’s collection was housed in his retreat on the Obersalzberg, Ryback writes insightfully about the layout of his office there with its magnificent view of the Unterberg, describing it as a place of “both refuge and inspiration.” (pg. 174) This was where all his great plans were conceived, as Hitler himself acknowledged. Ryback asks why he decided not to make his last stand there, and speculates that Hitler thought that if he had left Berlin as the Soviets approached, it would have looked like he was trying to escape. It was important to him not to be thought a coward, to die at (or near) the front. As he heard the sound of the approaching artillery bombardment in April-May 1945, it must have taken him back to the Western Front during the First World War. It comes as little surprise that at the end, Hitler had a collection of the prophecies of Nostradamus at his bedside in the bunker. Being an autodidact often goes hand in hand with a fascination for astrology and the occult.

Errata

Among the some 400 books Hitler checked out of the library in the early 1920s, one is listed here as Kant’s Metaphysical Elements of Ethics. (pg. 50) The work in question, Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten (1785) is usually translated as Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals.

Depending on the context, the German word Geschichten can mean either “histories” or “stories.” When referring to Hitler’s “oldest surviving book on Frederick the Great,” Ryback opts for the wrong one, as he refers to Histories and Whatever Else There Is to Report About Old Fritz, the Great King and Hero. (pg. 232, note) The whole flavor of the title tells us we are dealing here with popular stories and anecdotes, not tomes written by Ranke or Burckhardt.

Here’s a less than ideal translation he ignored. Carlyle, in his biography of Frederick, quotes the king as writing in his darkest hour, when all seemed lost: “the conclusion will come; and if the end of the piece be lucky, we will forget the rest.” (pg. 231) The passage is taken from the Chapman and Hall ed. of Carlyle’s History of Friedrich II of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great (vol. 4, book 20, pg. 438). Whether Frederick’s remark was originally in German or French, most likely he was alluding to the play’s “happy” (not “lucky”) ending.

Ryback deals not just with books Hitler acquired, but those sent to him by fans and presented by friends. Even if there is no evidence Hitler ever read them, they are included here – rightly so. For example: “The SS leader Heinrich Himmler gave Hitler two ideology-infused volumes, Voices of Our Ancestors in 1934 and Death and Immortality in the World View of Indo-Germanic Thinkers in 1938.” (pg. 119)

If one reads hastily, one might assume that Himmler himself was the author of these two works. In fact, it appears Die Stimme der Ahnen (lit. “The Voice of the Ancestors” though Ryback’s “Voices of Our Ancestors” is preferable) was written by one Wulf Sorensen. A little digging reveals that, remarkably enough, Sorensen, though himself a Nazi, was held by the Gestapo for some eight months in 1937-38 for the crime of insulting the Führer. Evidently he wasn’t the right kind of racist. He was released only on the condition that he refrain from publishing anything further without Himmler’s prior approval. As for the second book, Tod und Unsterblichkeit im Weltbild indogermanischer Denker was written by Kurt Schrötter and Walther Wüst, with contributions by Hitler and Himmler themselves, among others.

Admittedly these authors (and their titles) are obscure, but that’s partly an accident of history. Wüst, at least, was prominent in his day, delivering lectures to the SS on Mein Kampf as an expression of “Aryan philosophy.” During the war, he served as Rector of the University of Munich. When writing about a library, surely it is advisable to provide the authors’ names in addition to the titles, no matter how forgotten they may be. If things had turned out differently, their books might be required reading today.

Updates:

- “As is typical for many autodidacts, Hitler believed he knew better than specialists… and treated them with an arrogance that was but the reverse of his own limited horizons.” Volker Ullrich: Hitler: Ascent 1889-1939. (Oxford: Bodley Head, 2016)

- A secret dossier, prepared for Stalin from the interrogations of Hitler’s personal aides in the late 1940s, contains pertinent information. Take this example, from autumn 1942: “He picked up books like I Claudius, Emperor and God, which described the gruesome struggles around the throne of the Roman emperor, or a work on the campaigns of the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich Hohenstaufen in the thirteenth century.” (The Hitler Book, ed. Henrik Eberle, Matthias Uhl [NY, 2005]. pg. 88) Ryback mentions neither of these books; possibly they were not part of the collections he examined, or did not survive the war.

- Another book not mentioned is Hans Zöberlein’s nationalist tome, Der Glaube an Deutschland. This is of more than usual interest because in 1931, Hitler himself penned a foreword to it in which he refers to his experiences on the Western Front. (See Thomas Weber: Hitler’s First War, pg. 274)

- In January 2019 another book owned by Hitler surfaced when it was acquired by Canada’s national archive: Heinz Kloss: Statistik, Presse und Organisationen des Judentums in den Vereinigten Staaten und Kanada. Ein Handbuch im Zusammenarbeit mit Edith Pütter. Vertrauliche Schriftenreihe Uebersee (Stuttgart: Selbstverlag der Publikationsstelle, 1944). The book was probably removed from the Berghof in 1945. A picture of it shows Hitler’s ex libris. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/25/nazi-north-american-holocaust-book-canada-national-archive Among other books Heinz Kloss wrote during the Nazi period is Brüder vor den Toren des Reiches: Vom volksdeutschen Schicksal. (Berlin: Paul Hochmuth, 1942). After the war he enjoyed a long career writing about Germans abroad, particularly in North America.

- American eugenicist Leon Whitney received a personal thank-you letter from Hitler after sending him a copy of his 1934 book The Case for Sterilization. See Adad Serwer’s story on white nationalism in the March 2019 issue of The Atlantic. Also mentioned in the article are Henry Fairfield Osborn, who wrote the introduction to Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race and accepted an honorary degree from Frankfurt’s Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, and Harry Laughlin, who was awarded an honorary degree from Heidelberg University in 1936.

© Hamilton Beck