Milt Bearden, James Risen: The Main Enemy. The Inside Story of the CIA’s Final Showdown with the KGB. NY: Random House, 2003. 560 pp.

The Main Enemy reads almost like an espionage novel, full of drama and high-stakes scenes. Though it has not been turned into a film, co-author Milt Bearden has dipped his toe into both movies and television. He was credited as “CIA technical advisor” to “The Good Shepherd,” one of the best movies dealing with the Angleton era. And Hollywood knows how to reciprocate – the dust jacket of The Main Enemy features a blurb from Robert de Niro, who appears in “The Good Shepherd” as a fictional version of Wild Bill Donovan.

The Discovery channel has shown Bearden recounting his story of turning out the light in his Kabul office as the last Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan – for years he had left it on as a signal that he was working tirelessly to achieve their defeat. Although The Main Enemy pays a kind of grudging respect to Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson, mostly he appears as someone who grabs more credit than he deserves. Still, the message here is quite similar to that of “Charlie Wilson’s War” (in which Philip Seymour Hoffman plays a character much like Milt Bearden) – the US squandered its victory over the USSR. Once the last Soviet tank crossed that bridge, we lost interest and left a fractured country to the warring Afghan factions, with results that are all too familiar.

Though the Central Asian parts of this long but briskly-paced book have gotten the most attention, what I want to concentrate on here are the other locations, the ones set in New York, Washington, Moscow and Berlin.

To start with, here’s a rule of thumb that I have always found handy. When reading a book or article about the CIA, make a mental note of how many times the word “legendary” pops up. Because this word is a good indicator of something worth keeping in mind: Its presence is a dead giveaway that while the authors may be insiders, they lack the requisite distance to report objectively. Instead of writing history, they may be producing hagiography. As Kim Philby once said, “All intelligence people who achieve fame or notoriety… are elevated to legendary status – by their own side.” (Phillip Knightley: Philby KGB Masterspy, 2003, pg. 155)

In the present case, the first instance crops up early on: Spymaster Burton Gerber’s “exacting attention to the details of espionage tradecraft and his impatience with those who failed to meet his standards were legendary.” (pg. 4) Rem Krassilnikov, the model for John le Carré’s “Karla,” had established himself by the mid-1980s “as a legend.” (pg. 13) This is followed by a reference to “the legendary Penkovsky.” (pg. 27) The CIA station chief in Rome, Allan D. Wolf, is characterized as “diminutive but legendary” (pg. 73). While it may be appropriate to describe East German intelligence chief Markus Wolf as a “retired legend” and a “mythic figure,” it does seem a bit of a stretch to call Britain’s Prime Minister Asquith “legendary.” (pp. 440f, 68)

It’s hardly classified information, of course, that the world presented here is viewed from the top floors at Langley. The dust jacket describes Bearden as a “thirty-year veteran of the CIA’s clandestine services… chief of the Soviet/East European Division at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union.” While it is understandable that Bearden and co-author James Risen admire many of the agents they describe, the reader is left wondering how a number of them could manage to be both legendary and clueless. For it must be said the actions detailed here frequently reveal something short of total competence.

Take the disgruntled agent Edward Lee Howard, whose escape to Russia sealed the doom of the Agency’s greatest asset there, Adolf Tolkachev, or the bungled handling of the defector Vitaly Yurchenko. Langley’s Soviet Division officer in charge of Eastern European counterintelligence and one of Yurchenko’s main debriefers simply messed up when it came to his re-defection back to Moscow. That unfortunate officer was punished, but Gerber should have borne the responsibility, especially since he was also involved in the Howard disaster. Ultimately, of course, it was William Casey, Milt Bearden’s mumbling buddy, who was most at fault: “Casey did take the darkest stories of the Soviets at face value. Arguing against him could be dangerous for a CIA officer’s career.” (pg. 155) That’s about the strongest criticism of him to be found in this book.

So it should be clear that the authors are not exactly neutral, objective historians. Which is not necessarily a problem – readers can accept that fact and still enjoy the book for the inside information it reveals (or more accurately: that it has been cleared to reveal). But again, caution is advised. Take, for instance, the numerous dramatic conversations presented here. While they appear in quotation marks, neither they nor the many excerpts from secret cables should be treated as verbatim transcripts. “Where there is dialogue in the book, it corresponds to the specific recollections of one or more of the people present in the room. Beyond this, we have taken the liberty of reconstructing several CIA cables… these are not actual cables but are reconstructions by Milt Bearden based on his thirty years of reading and writing CIA cables…” (Foreword, pg. viii) In other words, the historical record has been trimmed and tightened, the script already primed for theatrical treatment.

That explains why there are no footnotes: After all, screenplays are not annotated. Some of the conversations presented here are “based on” recollections that may come from a single, unidentified participant remembering things many years on. As the “Note on Sources” reveals at the back of the book, this is fundamentally “an oral history based on hundreds of interviews with dozens of intelligence officers…” (pg. 537) None of whom, naturally, were motivated by anything as petty as the desire to make themselves look good in retrospect.

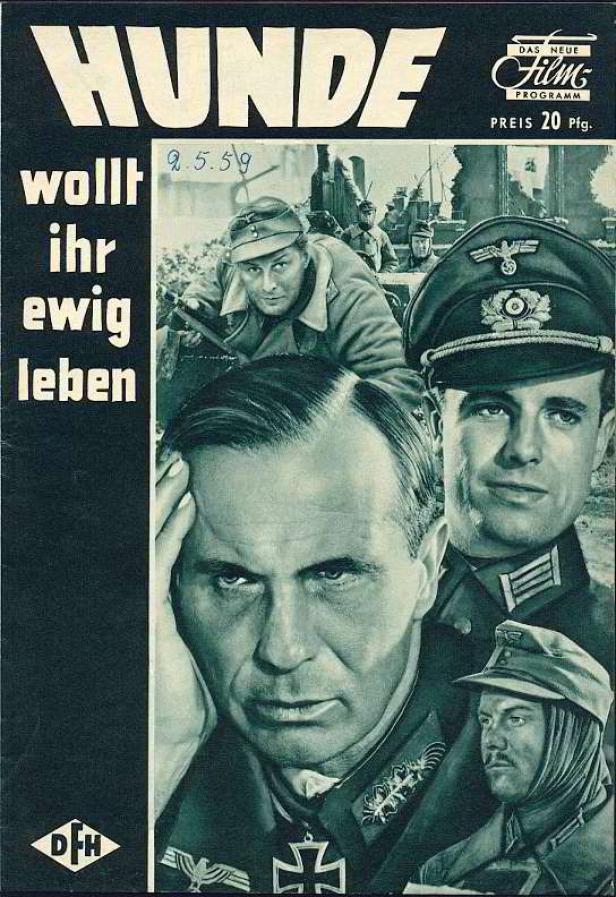

Finally, here’s another camera-ready scene. As the Warsaw Pact was collapsing and losing control over events, East German secret police chief General Werner Grossmann arranged a clandestine meeting with a CIA officer in East Berlin. The Stasi boss wanted to make an urgent personal request – that the Agency stop trying to recruit his men, who, facing imminent unemployment, were especially vulnerable. The officer reported this to Langley, and Bearden cabled back, saying: “… Your account was tremendously moving and almost reminiscent of the mixture of honor and fatalism shown by another generation of Germans at Stalingrad. Your General Grossman [sic] could have easily been von Paulus [sic]. About all we needed was a final message from the Fuhrer [sic] saying something along the lines of his last message to Paulus. ‘Huende [sic] wollt ihr ewig leben?’ [Dogs, do you want to live forever?]” (pg. 441)

Personally, I would be interested in knowing Grossmann’s version of this encounter, but I have not yet read his memoirs (according to reviews, he is unrepentant). Bearden, though, does include a historical reference that can be checked. And what does the record show? Not to be pedantic, but there was a movie about Stalingrad that appeared under the title “Hunde, wollt ihr ewig leben” (1959, written and directed by Frank Wisbar, based on a ca. 600-page novel with the same name by Stalingrad veteran Fritz Wöss). Press accounts confirm that the title was adapted from something Frederick the Great supposedly said (the story may be apocryphal) as his grenadiers streamed past him after the battle of Kolin in 1757: “Dogs, do you want to live forever?” Critics found the title the most provocative thing about the movie. The point is that nobody suggests that Hitler said anything like this, as the briefest of searches would have revealed. See Der Spiegel, “Stalingrad. Frei nach Schiller” (April 15, 1959). https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-42625075.html

In fact, the actual wording of Hitler’s last message to Paulus was: “The 6th Army will hold its positions to the last man and the last round.” Like the accurate versions of various German names and words (four errors in two lines is rather a lot), this detail would have been easy enough to check before publication, but the author evidently couldn’t be bothered. The legend was simply too good. (For what it’s worth, Oliver Stone also refers to “von” Paulus in his Untold History of the United States, chpt. 1. Friedrich Paulus was not born a member of the nobility and never became one.)

These may seem minor points, but Bearden’s hazy grasp of detail, combined with certainty of his rectitude and a flair for the dramatic – all this does not exactly inspire confidence in his accuracy. For if he can’t be bothered to verify his own quotes, what other parts of this history might be equally dubious? What other facts may have been distorted for the sake of creating a good yarn? In sum, the reader is left with a wealth of information that cannot be checked, marred by a rather hyped presentation.

Update

Right after the scene with General Grossmann comes one with the former head of East German counterintelligence, Markus Wolf. According to Bearden, the purpose of Gus Hathaway’s visit to Wolf’s dacha outside Berlin was “to get him to shed light on the terrible losses the CIA had suffered five years earlier.” Wolf politely refused. “After that brief meeting, no one ever returned to see if Markus Wolf had changed his mind.” (pg. 442)

In his memoirs Man Without a Face (which came out some six years before The Main Enemy), Markus Wolf presents a rather different version – one that is not only much more detailed, but based on tape recordings he made of their conversations. According to Wolf, the purpose of the first visit was not simply to shed light on past events, but to beg for assistance. When Hathaway, after some encouragement from Wolf, finally got around to the point of his visit, he stated flat out: “We are looking for a mole inside our operation. He has done a lot of damage. Bad things happened to us around 1985.”

From this and other remarks, Wolf says, “I guessed that there had already been some painstaking research at Langley into my cooperation with the KGB and that this had raised hopes that I might know the identity of the mole they sought. I did not…. It was clear from Hathaway’s earnest approach and tenacious attempts to lure me into the American camp that the CIA was in a state of panic about its penetration. They must have swallowed hard to bring their problem to me.” (pg. 14f.)

The sense of urgency is underlined by the fact that, far from there being no follow-up, the invitation was renewed on three subsequent meetings – two at his dacha, the last at his apartment in East Berlin. But since they brought “no improvement in the American offer,” Wolf ultimately declined to cooperate. “When the story of Ames’s treachery emerged, I was stunned that he could have carried on undiscovered for so long and that American counterintelligence proved so incompetent and desperate as to be forced to resort to the help of an enemy spy chief to find him.” (pg. 18)

Overall, a fuller picture of Gus Hathaway’s fundamental decency and humanity emerges here, in this account from a former adversary, than from his agency colleague Milt “Hollywood” Bearden.

© Hamilton Beck