Langston Hughes: The Big Sea. The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, Vol. 13. Edited with an Introduction by Joseph McLaren. Columbia and London: Univ. of Missouri Press, 2002. 268 pp.

This autobiography begins with the author sailing out of New York harbor and chucking his collection of books overboard, “as far as I could out into the sea.” (pg. 31) The last chapter of part one explains why: “They seemed to me too much like everything I had known in the past… like life isn’t, as described in romantic prose…” (pg. 93)

In between we learn about his education, both in and out of the classroom. His Jewish friends at Central High in Cleveland “were almost all interested in more than basketball and the glee club. They took me to hear Eugene Debs. And when the Russian Revolution broke out, our school almost held a celebration.” (pg. 49) Armistice Day, when Hughes was 16, did bring celebrations on the streets. “But many of the students at Central kept talking, not about the end of the war, but about Russia, where Lenin had taken power in the name of the workers…” (pg. 63)

The summer of 1919 he spent in a village in the mountains of Mexico; this would have been idyllic except for his ever-critical father, whose minimal parenting skills consisted mainly of being miserly and barking at his son to hurry up. James Nathaniel Hughes admired the German people much more than he did his black fellow-Americans, going so far as to learn to speak the language. He eventually married the widowed German housekeeper he hired after the war’s end. Readers can find out his eventual fate in the next volume, I Wonder as I Wander.

Young Langston supplemented his meager allowance by working as a TOEFL teacher in a local village. Using the Berlitz method, he was so successful that word got around and he was hired to give lessons at a business college and a finishing school for girls. One wonders how they fared with his replacement, a “gringa” from Arkansas, a state that proved to be the home of some of the most virulent racists he would encounter, including some missionaries in part two.

This begins in 1923 with his decision to ship out to the west coast of Africa. “It was the only place in the world where I’ve ever been called a white man” because of “my copper brown skin and straight black hair” – plus his American citizenship. In terms of contemporary political correctness, it is interesting to read that “a dark-skinned minister in New Jersey denounced me to his congregation for using the word ‘black’ to describe him in a newspaper article….” It was at that point that “I realized that most dark Negroes in America do not like the word ‘black’ at all…” (pg. 96)

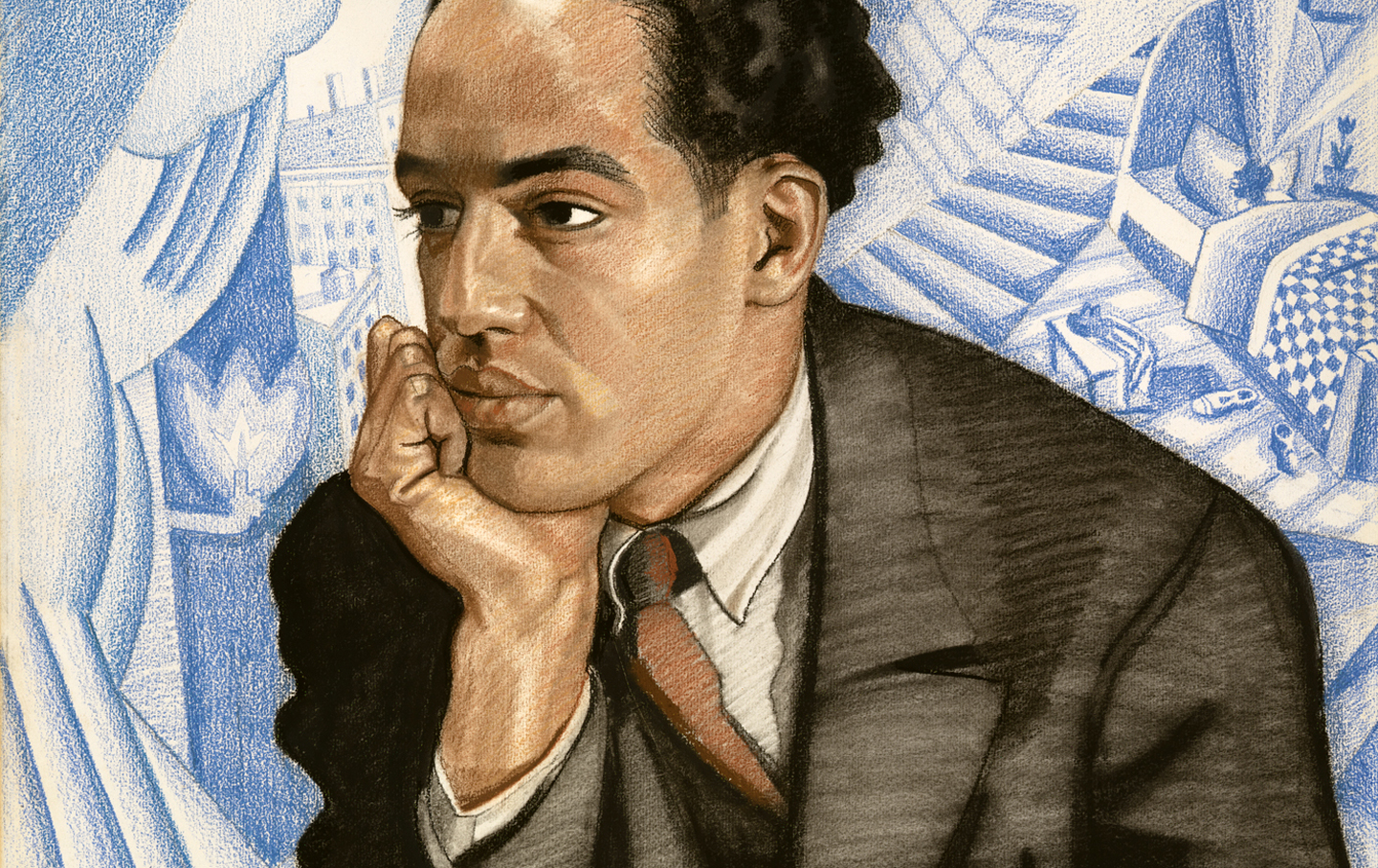

(Painting by Winold Reiss, in the National Portrait Gallery)

The story of his life is in large part the story of his travels. In 1924 he sailed for Europe, eventually arriving in Paris with seven dollars in his pocket and no place to stay. Survival demanded that he develop a talent for living on little or no money. His high-school French was good enough to read the signs but left him unable to understand the language as spoken by Parisians. Since he had never learned to play an instrument or tap dance, only menial restaurant jobs were open to him. Fortunately, he met a Russian ballet dancer, Sonya, who helped him find a room he could afford. At first this seemed an example of “the quick friendship of the dispossessed,” though as it turned out he would have to share the tiny room with her. (pg. 128) Later that year he arrived back in New York with only twenty-five cents in his pocket – and it’s not like he had made and lost a fortune in the interval.

The final part, “Black Renaissance,” deals with Manhattan in the late 1920s and early ’30s, a period when “white writers wrote about Negroes more successfully (commercially speaking) than Negroes did about themselves… It was the period when the Negro was in vogue” and “Harlemites” thought “the race problem had at last been solved through Art plus Gladys Bentley.” (pg. 178) Later he ventured south for the first time, taking the train through Vicksburg to New Orleans, where he rented a room in the French Quarter. “It was a picturesque house. But like most picturesque things out of the past, not very comfortable, only beautiful to look at.” (pg. 222)

He returned by car, passing through Georgia in the company of Zora Neal Hurston. In this part, we are treated to a hodgepodge of topics, including amusing hand-painted road signs he observed, segregation at Lincoln University, and his troubled relationship with his New York patron, Charlotte Osgood Mason, who wanted him to write in the style of a primitive African. Fundamentally this did not suit him. Poetry, for him, was a form of therapy, something he composed to alleviate his unhappiness. The volume concludes with his resolve to choose writing as a career, for literature is “a big sea.” (pg. 252)

One drawback: the author is not shy about rattling off lists of famous or once-famous people; this is especially true in part three, which features name after name. I can well imagine that if you had known Hughes in Harlem but failed to find yourself mentioned here, you might have taken offense, since at times it seems as if he was determined to omit no one.

This problem is compounded by the editor, whose minimally helpful notes follow the motto, “The less you know the sounder you’ll sleep.” While there is no harm in reminding us who Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were, lesser mortals are consigned to oblivion, along with the drums of Omah and the Ju-Ju (apparently part of voodoo ritual).

In sum, one comes away impressed not only with the author’s good common sense and his hands-on approach to life’s problems, but above all his fundamental decency and gentleness. As for his writing itself, his style can perhaps best be characterized in negative terms as avoidance of jargon and abstruse theorizing, in positive ones as understated elegance.

© Hamilton Beck

Update: You may also be interested in my review of the second installment of Langston Hughes’ memoirs, I Wonder as I Wander, elsewhere at this site. Also Du Bois in Germany, 1892-94.

See also Yuval Taylor: Zora and Langston Hughes: A Story of Friendship and Betrayal (NY: Norton, 2019); an extended excerpt appeared online at Longreads under the title, “When Zora and Langston Took a Roadtrip.” At the Tuskegee Institute’s summer school, he “read a number of his poems, and described his travels in France and Africa.”