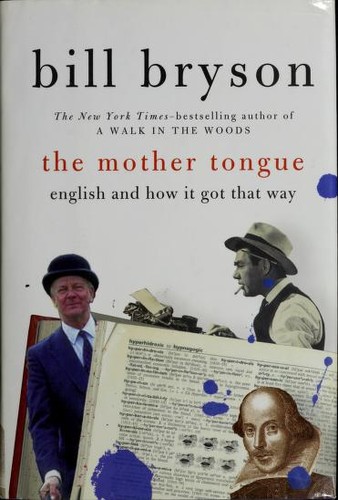

Bill Bryson: The Mother Tongue. English and How it Got that Way. NY: Perennial, 2001. 270 pp.

Bill Bryson has carved out a niche for himself as a popular travel writer with an interest in language. In The Mother Tongue, he has written a book that is engaging, easy to read (and re-read), and not terribly reliable. It’s not that he makes stuff up, it’s just that – lacking any specialized training as a linguist – he is irresistibly drawn to the colorful anecdote and the amusing tale. Likewise he is not first and foremost a fact-checker. Rather, he is content back up his assertions about language by citing sources including The Economist and Time magazine. If an allegation has been printed there that jibes with his thesis, he repeats it, though he rarely bothers to inquire into whether it has been debunked. His overriding goal, after all, is not to ascertain the truth but to sell enough books to earn a decent living.

Most people produce and consume their native tongue without giving it a second thought. For Bryson, though, language is a source of delight. He has collected such a treasure trove of odd facts that he can effortlessly trot out one amusing example after another. It seems petty to single out a dubious one and subject it to close examination (do the Eskimos really have fifty words for snow?). Bill Bryson should never be confused with an authority on linguistics. He is instead a diligent collector of entertaining stories, a good number of which might well be true.

The chapter on English as a World Language, for example, includes examples culled from foreign advertisements and menus, an inexhaustible source of merriment. I challenge any native speaker to read this section without laughing out loud, or at least breaking into a smile. My personal favorite: Hand-Maid Queer Aid, a Japanese brand of chocolate. This is the sort of humor that a native speaker could never come up with but that non-native speakers create effortlessly, if unintentionally.

When an amateur writes about a technical topic, the result is likely to be popularization. The professionals should not criticize him for lacking scientific rigor, for that is a standard to which he does not aspire. Bryson seems most reliable when it comes to comparing American and British usage; even here, his field research, such as it is, appears to have been conducted chiefly in the streets and pubs of Yorkshire. Still, he manages to show that the routine denigration of Americanisms is often based on misinformation, as many of the alleged barbarisms, far from being recent imports, in fact existed for centuries in England.

For the most part, Bryson is content to cover familiar, expected topics: words whose meaning has changed (sometimes radically), the on-going war between the pre- and descriptivists, Shakespeare’s contributions to the language, and so on. And there is no doubting his point that “English has become the most global of languages.” (pg. 12) How did it get that way? Like most people who attempt an answer, he tends to think that the spread of any particular tongue – or its disappearance – depends on some innate features; in the case of English, on the “subtlety and flexibility built into the language.” (pg. 51) Yet dozens of languages spoken by Native Americans, for example, did not decline and die out because they were insufficiently flexible, but because their speakers were rounded up, decimated, and sometimes exterminated. English survived both the Viking raids and the Normal conquest not because of the subtlety of the language but because enough speakers of it managed to survive and propagate themselves.

Like many writers who fall in love with a particular tongue, Bryson thinks its continued existence and eventual triumph must be due to something intrinsic, such as its flexibility, rather than the success of its speakers at reproducing themselves and spreading their dominion. The growth or contraction of a particular tongue depends mostly on factors such as geography, history and population. This elemental truth is overlooked by those who promote their favored language and attribute its success to some essential virtue they claim it possesses uniquely.

The spread of any language has little or nothing to do with its inner qualities, and everything to do with factors such as international commerce, colonization, and the projection of maritime power. Has Bryson not heard the adage that a language is a dialect with an army and navy? If either Russia or Germany had been a sea-going power from the 16th century on, the linguistic map of the globe would look very different today. The reason Spanish is spoken across so much of South and Central America has precious little to do with the peculiarities of the Spanish language.

Bryson gives no hint of holding American exceptionalist views. Indeed it would be hard to hold such views and live abroad as long as he did and emerge unscathed. I’m sure he would concede, for example, that both Russian and German orthography are much more logical. Nevertheless he does hold to a kind of English-language exceptionalism. Not that he claims English is more beautiful, but he does assert it is unusually open to change. And who knows, perhaps there is some truth to this. He posits that another reason it has spread across the world is because of its rich vocabulary (evidenced by the need for the thesaurus). English allegedly has 200,000 words in common use, compared to 184,000 in German and a mere 100,000 in French.

Yet skeptical readers would like to see greater evidence of close familiarity with a range of other tongues. It’s easier to sell English-language exceptionalism when you are writing for an audience that is overwhelmingly monolingual. Without openly pandering, Bryson is able to flatter his readers by assuring them that they are speakers of a great language – maybe the greatest ever. Just look at how fruitfully we multiply new expressions and how eagerly they are taken up by a grateful world. Well okay then!

It is regrettable that Bryson rarely strikes out on his own in search of answers to offbeat questions. Like this: Has he never wondered where, for example, the innocuous expression “all of a sudden” came from? If we can have “all” of a sudden, why not “half” or “most” of a sudden? When did “sudden” become a noun anyway, and a countable one at that? Why can’t we say, at least theoretically, “all of half a dozen suddens”?

Another question: It’s generally assumed that Eve, our original common ancestor, spoke an Ur-tongue from which ultimately all languages derive – even though there is no evidence that there was a unique first speaker at all, or that she spoke. (Who would she have spoken to anyway?) David Bellos calls it “a single barely questioned assumption – that all languages are, at bottom, the same kind of thing, because, at the start, they were the same thing” (Is That a Fish In Your Ear. Translation and the Meaning of Everything [NY: Faber and Faber, 2011], pg. 327) – an assumption which Bellos goes on to question. But even assuming monogenesis, that is, a single origin for all varieties of speech, one wonders how large Eve’s vocabulary was. Did her grandkids think she spoke with a funny accent, or used quaint expressions? Jumping ahead a few years, it’s widely believed that Neanderthals used language. Has anyone thought to speculate on just how many Neanderthal dialects there might have been? Did they need translators?

It’s generally agreed that Indo-European began to break up into separate languages about 3500-2500 BC. Bryson never poses a question that has long interested me: At what point in history were the greatest number of languages in existence? This has always struck me as a rather basic statistic that writers on this topic should want to know. We regularly hear about the death of yet another obscure tongue whose last speaker has lamentably passed away, her final words lost to posterity forever. As George Steiner puts it in his typically orotund fashion, “Almost at every moment in time, notably in the sphere of American Indian speech, some ancient and rich expression of articulate being is lapsing into irretrievable silence” (After Babel, 3rd ed. 53). It would seem to follow that the total number of languages must be decreasing. So we started with (presumably) one language in pre-historic times, and obviously have a larger – though declining – number today. Currently, according to Bryson, there are about 2,700 languages extant, more than half of them in a single county – India. His critics have put the number much higher. About a thousand languages were spoken in the New World when Columbus stepped ashore; today there are guess-timated to be about 600 of them left, but nobody is sure of the exact figure. In any event, to my knowledge no one has ever calculated, even approximately, when the zenith was reached. Were more languages in existence in the age of Horace or of Horace Greeley?

Bryson does make a good point that “unlike other borrowing tongues, we are generally content to leave foreign words as they are.” (pg. 128) The advantage: In English, foreign words and expressions remain obviously foreign. The disadvantage: We may not know how to say them by looking at them. The problem is reversed for Russians. They can pronounce “chef d’oeuvre” correctly, but when spelled in Cyrillic it is not obviously French to the untutored Russian reader.

In sum, while critical reviewers have taken issue with this or that claim, few have challenged Bryson’s central assertion, namely that there is something special about English itself that explains its current preeminence. Over the years, a consensus has emerged that The Mother Tongue is amusingly written and bursting with fun facts. The chief disagreement is about whether the errors are so numerous as to make the book unreliable, or whether they are inconsequential because after all it is not a reference work. Some have noted the contradiction between his repeated assertions that English is not inherently better than any other language, and his parallel argument that English has unique advantages when it comes to adaptability and generating new forms. What has been overlooked is the narrowness of his view, as though the spread of English can somehow be explained as a function of innate qualities of the language itself. He refuses to acknowledge that, to oversimplify a little, English is the world’s most popular second language for the same reason the dollar is the world’s most popular reserve currency.

Update 1: Many of the same points are made by John McWhorter in his review of Robert McCrum’s popular Globish: “McCrum is taken with a notion that there is something about English itself that has gotten it to this point [where English is spoken everywhere] …. Deep down he likes the idea that English is somehow inherently handy, fundamentally ‘universal’ as he puts it here and there. …. McCrum’s sense that English is somehow uniquely ‘direct’ and ‘universal’ and therefore well-suited to bestride the world is false…. Both English and Russian have spread the way they have because they were the languages that happened to be spoken by powers that happened to acquire vast amounts of territory.” See: “Is English Special Because It’s ‘Globish’?” The New Republic, June 21, 2010.

Update 2: “It is unlikely that Australopithecus (who first appeared around 4-5 million BC) could speak, but the evidence is ambiguous for Neanderthals (70-35,000 BC).” David Crystal: How Language Works (2006, pg. 354) As a rule of thumb, such guesstimates usually get pushed in only one direction – ever further into the past.

Update 3: According to Steven Pinker (Words and Rules, 1999, pg. 67) , Proto-Indo-European was a single language that began to break up into different languages around 7000 BC. Or maybe closer to 3,500 BC. Who’s to say? And what does a difference of three and a half thousand years amount to anyway?

Update 4: “Eskimo is not a language but a group of them, comprising the Inuit and Yupik families, spoken from Greenland to Siberia. Nor, as the linguist Geoffrey Pullum explains, are Eskimo languages actually especially rich in snow terminology. What they are rich in is suffixes, which allow their speakers to build endless variations upon a small base of root words. (If you’re tallying derivations, Eskimo languages also have a multitude of words for sun.) Sticking strictly to lexemes, or minimal meaningful units of language, Anthony C. Woodbury has catalogued about fifteen distinct snow words in one Eskimo language, Central Alaskan Yupik – roughly the same number as there are in English. A cartoon, mocking our credulity, features two Eskimo speakers. One asks the other, ‘Did you know that in Hampstead they have fifty different names for bread?’ ” Lauren Collins: “Love in Translation” (The New Yorker, August 8 & 15, 2016, pg. 58)

Reviews of books of related interest elsewhere at this site: David Crystal: Stories of English; Ben Yagoda: Sound on the Page and When You Catch an Adjective, Kill It; Stephen King: On Writing.

© Hamilton Beck