Betty Roland: Caviar for Breakfast. A Russian diary. Melbourne, London, New York: Quartet Books, 1979. 196 pp. Ill.

The Journey Begins

Caviar for Breakfast starts as a love story, with the heroine and her white knight eloping in the portentous year of 1933. Complications rapidly ensue. The first: Betty Roland is already (unhappily) married. A second is that the man she runs off with, Guido Barrachi, is a lapsed Catholic and idealistic Communist; his first gift to her is a copy of the Communist Manifesto. Given these circumstances, the fact that he is also married appears merely as “an extra complication.” (pg. 6)

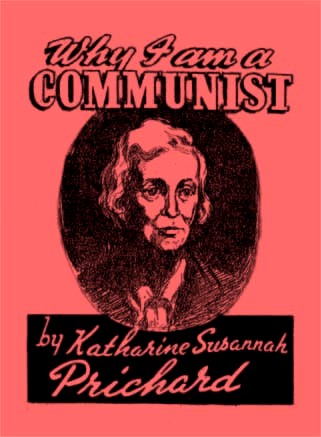

Before leaving Australia, they meet Katharine Susannah Prichard, described as “One of Australia’s most celebrated writers” and “the Maxim Gorky of Australia.” Over dinner at Greenmount, they also meet her husband, a veteran of the Great War. “How did Katharine, dedicated Communist that she is, come to marry a man like Hugo Throssell? What have they got in common? She has no respect for soldiers and a Victoria Cross to her is not so much an award for valour as an indication that the recipient is an expert at killing other men.” (pp. 8, 9)

Betty and Guido’s departure is more of an escape than a romantic voyage via the Suez Canal to London. Once there, she is introduced to more celebrities, in this case the leaders of the British CP, including Palme Dutt and Harry Pollitt – contacts she would renew later.

Their personal situation begins to clear up a bit when her Guido’s wife Neura agrees to go back to Australia, leaving him free to proceed with Betty. The abandoned wife presents the author a farewell gift, a book with the inscription: “To Betty, with comradely good wishes for every happiness and success in the USSR. Neura.” (pg. 11)

The couple sets sail again, booking rooms on the Felix Dzerzhinsky. Arriving at the port of Leningrad, all the passengers spontaneously burst into revolutionary song, and she compares them to pilgrims arriving in the Holy Land.

From that point on, disappointment gradually sets in. A first discordant note: The sadness that overcame her while leafing through photographs of the Czar’s murdered family at the Catherine Palace. Guido, a much more orthodox Communist, disapproved of all the “decadent” finery to be found there. (pg. 23)

In Moscow

The couple did not stay long in Leningrad, traveling on to Moscow, the Mecca of Marxist brotherhood. Arriving in time for the May Day celebrations, they were treated as guests of honor and allowed to observe the parade from near the Lenin Mausoleum.

Though it meant overstaying her visa, Roland soon landed a job at the Moscow Daily News, while Guido found work as a translator. Disillusionment grew as they looked for new accommodations: “… we were led down to the communal kitchen in the basement. It was vast and dark and unspeakably depressing. ‘My’ section consisted of an upended packing-case and two reeking kerosene stoves. On these I was expected to cook, boil up the washing and, in all probability, heat water for an occasional bath taken in a basin in the room above. Also, having cooked the meal, I would have to carry it up three flights of stairs. There was one sink in a corner of the room, a dripping tap, and nothing else in the way of amenities. Several women were busy on their stoves; they stared at me with hostile eyes, already regarding me as an interloper. If my expression was an indication of my feelings it must have been one of horror.” (pg. 50)

It is in this section that the title is explained: “… each morning, we have to rush through breakfast which consists of milkless tea, rye bread with a scrape of margarine or butter and, quite frequently, caviar. It amuses us that, in this land of hunger and general want, caviar is plentiful and so cheap that it replaces marmalade for breakfast.” (pg. 62)

Like many visitors to Russia, she was struck by the polite treatment of foreign guests. “There have been times when I have been standing in a queue and been beckoned to the front, merely because I am a stranger, therefore, in a sense, a guest. Sometimes, in an overcrowded tram (and what tram is ever otherwise?), someone will get up and offer me a seat and look quite upset if I refuse it. There is no resentment because my clothes are better and I am better fed, it even seems to give them pleasure. They are lovable people, the Russians, kindly and warmhearted, the more I see of them, the more I like them. And their patience in inexhaustible. They stand in queues for hours, stoically resigned to cold or heat, to discover all too frequently that the kerosene or flour or potatoes they had hoped to buy has all been sold.” (pp. 66f.)

A few pages later, she observed how different things were for locals in public transportation. “I once saw a woman waiting at a tram stop; she had a sack of potatoes lying at her feet. When the tram arrived, she heaved it onto her back and climbed on board. How she managed to do so, considering the already over-crowded condition of the tram is a mystery, but by dint of a great deal of pushing and shoving, she accomplished it, stoically ignoring the chorus of abuse the displaced passengers hurled at her.” (pg. 76)

They heard stories about famine in 1932, the year before their arrival: “… the crops failed for lack of rain and what yield there was largely went unharvested by the rebellious peasants who resented collectivization. This year things are different. The malcontents were severely punished, the best Party organizers transferred from the factories to the country to supervise the ploughing and the sowing, the rain came at the right time, and a bumper crop is the result. So there should be bread for everyone quite soon.” (pg. 71) Still, the numerous beggars on the street were hard to ignore.

Return to Leningrad

In general, Roland gives a vivid sense of what it was like to be in the USSR on the eve of the great purges. She was still idealistic at this stage, though with growing reservations.

After arriving back in Leningrad in time to join in the celebration of the October revolution, she again had to cope with the pervasive shortage of housing. In the Leningrad Hotel she shared a single room with twenty other guests. From there she moved to a converted monastery far outside town, a place infested with bedbugs and toilets “best left undescribed.” (pg. 89)

After hiring a horse and wagon, once again they relocated to a new abode. The moving men pilfered all their food – even pouring the sugar into their pockets and gulping down the remains of a pot of jam when no one was looking. One of these “merry-looking rascals” devoured their breakfast egg right in front of them. She and Guido did not begrudge it under the circumstances. (pg. 95)

While they did not witness any show trials per se, they did attend a Communist party cleansing session. A colleague at the publishing house where she worked was expelled “because she had failed to give the correct answers to questions on Marxist theory…. The all-powerful Party has its terrifying aspects and even Guido seemed a little shocked by this ruthless treatment of a loyal member.” (pg. 111) Expulsion from the CP had serious consequences, since it meant a loss of food privileges.

To top things off, thieves broke into their apartment and made off with literally everything, including even the sheets and blankets from the bed. The only item not stolen – her diary, on which this book is based.

To London and Back

Replenishing their supplies meant returning to London, at least for her. On crossing the German border in 1934, she describes her reaction upon seeing stores filled with goods as one of pure delight. “Too excited to sleep, I gave up the attempt, got out of bed, dressed, and wandered round the streets, feasting my eyes on the shops, marveling at the well-dressed crowds and the air of affluence that I had almost come to believe did not exist. If this was Capitalism, there was a good deal to be said for it.” (pg. 130)

In London, she encountered difficulties because she had initially gone to the Soviet Union on a 21-day visa and then stayed most of a year. Oddly enough, the awkward questions came not from the British authorities but from Intourist officials, who interrogated her closely when she tried to book her return. How could she explain that she had arrived as a tourist the previous year, but then found employment? The hurdles only seemed to grow and eventually she began to wonder if the theft of all their possessions in Leningrad had not been part of a conspiracy to get her to leave the country and then prevent her return.

In desperation, she turned to her old acquaintance Harry Pollitt for advice. Though known as “a notoriously rough diamond,” (Stephen Koch: Double Lives, pg. 191) he advised her to see Ivan Maisky, Moscow’s representative in London, who proved helpful in eventually getting her the visa. “Even a Soviet Ambassador is not proof against a woman’s tears.” (pg. 138)

(A Soviet stamp honoring Harry Pollitt, 1970)

Once it became clear she would be allowed to return, Pollitt and Palme Dutt handed her a parcel of books and a large sealed envelope. Her description of how she managed to smuggle these items across the German border is one of the high points of the memoir. Effectively functioning as a courier bearing “Revolutionary material,” she vividly describes her emotions on the train. “I now felt partly paralysed and my mouth and throat were dry…. Then, like one walking in a dream, I moved into the corridor and waited for the next development…. I hoped I showed no sign of the panic that I felt. Thoughts went racing through my mind. The contents of the envelope might be innocuous, but that seemed unlikely….” (pg. 141)

In the end, she was saved by circumstances – the crucial packet was concealed in her coat sleeve and the German customs officer lacked the time to search her thoroughly because at the critical moment, the train reached the border and he had to exit before completing his inspection. As one who long ago made similar border crossings myself (into the GDR – though I carried no secret messages, merely books such as Animal Farm), I can well understand her apprehension, if that is the right word. “Semi-paralyzed with fear” is more like it. (pg. 142) In the event, her bourgeois appearance – the very thing that initially made Harry Pollitt suspect her – ended up helping her, since it functioned as a disguise. “Couriers – note well – are often selected precisely for their innocence. The reason is simple: The ignorant, if caught, will have nothing to say.” (Stephen Koch: Double Lives, pg. 161)

Upon her safe arrival in the USSR, she discovered that her anxiety had been well grounded. Though the books entrusted to her were harmless, the packet really did contain incriminating papers – and there was an officer from OGPU waiting at the border to take immediate delivery. Naturally, we never find out what was in those documents.

Supporting Cast

While the impressions the author forms about life in the Soviet Union are not that unusual and can be found in many books written by travelers of that period, what is striking is the cast of characters she encountered.

While working for the Moscow Daily News, Roland met journalist and author Anna Louise Strong, who made a strongly negative impression: bossy, jealous, and constantly stuffing her pockets with food she pilfered from banquet tables.

Those interested in Freda Utley will find a wealth of information about her here. Still an enthusiastic supporter of Communism at that time, Utley also worked at Moscow Daily News before undergoing the ordeal of two botched gynecological operations – performed without anaesthetic. This was followed by the arrest and execution of her Russian husband, events which led her to leave the Soviet Union and declare her support for the 1938 Munich Agreement. She shifted so far from her original beliefs that she came to view Hitler as the lesser evil, and ended up in the crackpot section of the extreme right wing, criticizing Joe McCarthy only because she thought he gave anti-Communism a bad name.

(Freda Utley in 1943)

Certain personages are identified only by first name or bland pseudonym: Jason, Joe, and John along with some that are more inventive, but who were Donnelly, Noffke, and Somerset? One can easily imagine various reasons why their identities are concealed (to protect them from the Soviet authorities, or perhaps those of their various homelands), but it is somewhat frustrating that no explanation of any kind is given.

She memorably describes an evening in late 1933 with a woman she calls “Madame Anitchkova,” an elderly aristocrat eking out a meager existence in the attic of her own former home in Leningrad. (If they made a movie of this book, I could see Tilda Swinton reprising her role as the aged dowager from “Grand Budapest Hotel.”) Her husband had once – obviously in pre-revolutionary days – been “Ambassador in Paris.” (pg. 105) Call me a pedant (as my esteemed professor Bob Chase used to say, a pedant is someone who likes to get his facts straight, and what’s wrong with that?) – but there was no Russian ambassador to France named “Anitchkov.” The last one before the revolution was Alexander Izvol’skii; so perhaps this was his widow. One can also make guesses about the grand building in whose attic she lived, very likely the Anichkov Palace.

(Anichkov Palace and Anichkov Bridge across the Fontanka, St Petersburg)

After the Revolution and until 1934 it housed the city museum, was reconstructed in 1936-37, then became the Palace of Young Pioneers. Perhaps the reconstruction took place after the death of the woman described here as “Madame Anitchkova.” The possibilities are intriguing, but alas, the cautious author does not provide enough information to enable us to make well-informed guesses.

Having spent about a year in the USSR, Betty and Guido decided they could not face another winter there. On their way out via the Caucasus (it seemed advisable to take the southern route), they ran into Joseph Kennedy, Jr., the eldest of the Kennedy brothers and the one his father thought mostly likely to become president. Joe Jr. was studying at the London School of Economics and spent the summer of 1934 in the USSR as the guest of US ambassador William Bullitt. Since the Wikipedia entry on him has little to say about this period in his life, Roland’s impressions are a valuable contribution.

Take this vignette of him from the Livadia Palace in Yalta. “The day that we were there a note of gaiety was introduced by the arrival of young Master Kennedy who came galloping up the road on a rather fractious horse. He was followed by the manager of our hotel, who seems to have been instructed to keep him out of harm’s way and is having considerable difficulty in doing so…. Young Joe adds greatly to our enjoyment of Yalta by his irrepressible good humour, his infectious laugh and total disregard for rules and regulations. (Soviet!) Catching sight of us, he reined his horse onto its haunches, scattering gravel right and left, raised one arm above his head and shouted ‘Heil Hitler!’ at the top of his powerful lungs.” (pg. 169)

As for Katharine Susannah Prichard, whom Roland had been introduced to at the beginning of her adventure, they met again when Prichard embarked on a tour of the Soviet Union. This involved an excursion to Siberia, from which she returned quite disillusioned, though exactly what went wrong is left somewhat obscure. Whatever happened, she came to appreciate her husband, who had remained behind in Australia. “This was a different Katharine and I contrasted her with the Katharine of that day at Greenmount. Her manner had been a little patronizing to Jimmy [Hugo Throssell] then, she had been inclined to brush him aside and he had been uneasy, nervous, excluded from the things that she and Guido had discussed. Now she has learnt to recognize his worth and I do not think that he will ever feel humiliated or excluded again.” (pg. 97) Their story, alas, does not have a happy ending.

(Hugo Throssell with his wife Katherine Susannah Prichard and their son Ric.)

Room For Improvement:

Roland says the famous Amber Room in Catherine Palace near St. Petersburg was a gift to Russia from “King of Sweden” – in fact, it was given by the King of Prussia, in 1716. Possibly the tour guide provided erroneous information. (pg. 22)

The Russian for “I love” is not “Ya Lubilou” but “Ya Lubliou” – think “yellow blue.” (pg. 43)

She says the scenes for the Mosfilm movie “Road to Life” were shot at “the monastery of Lyuberets” which had been converted into a home for homeless children. (pg. 80) There is indeed a monastery there, which survives to the present day: “Николо-Угрешский” in the town of Dzerzhinskiy (Lyubertsy district). The scenes used in “Road to Life” were not filmed there, however, but on the territory of the Annunciation Monastery in Sarapul.

Throughout the book, Roland often refers to pictures she took, but as far as I can tell none are among the ones reproduced here. It is true that her camera and pictures were stolen in Leningrad, along with all their other possessions, but afterwards she got another camera and resumed her photography. Almost the only private pictures included here are of documents (letters, etc.). Most of the rest are from publicly available sources such as Sovfoto and National Geographic.

Readers may also wish to look at my review of Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander, elsewhere at this site.

© Hamilton Beck